Connectedness & Community Gathering

Friday, September 9th, 2022

Perspective

In the 1930s, a group of researchers funded by department store magnate Grant began tracking Harvard graduates. Few decades later, the director of the study was able to make it clear that social connections play a crucial role in promoting a healthy and long lifestyle. Community is “what keeps us happy and healthy. Period.”

Relationships are the single most significant predictor of a person's success in life, according to George Vaillant, the longtime director of the study. It is not just important for your wellbeing and professional success that you maintain healthy relationships, but they may also be the key to your survival.

More recently, Brigham Young University conducted a study in which a broad range of variables, such as food types, exercise habits, and social behavior, were examined. Once again, strong relationships and a sense of belonging to a community are at the top of the list. It has been shown that a person's social connections have a greater impact on their life expectancy than their usual daily habits, such as eating, drinking, and smoking.

Yes, potentially even more than not smoking.

Why Gather?

These challenges aren't insurmountable.

A Sustainable World, Created Through Collaboration

Creating a world that values purpose, productivity and preference isn't something that can happen overnight. It will require not only hard work and perseverance, but also a deeply rooted collaboration with organizations who value the possibility of a better tomorrow over the profits of today.

THE WALDEN GATHERING Searched to review, explore & answer the following questions:

What is inclusion?

How can nature act as a catalyst for inclusion?

How do we create community?

How do we make Walden Gathering more inclusive?

“The need for connection and community is primal, as fundamental as the need for air, water, and food.”

Gathering Discussions

setting the tone through INTRODUCTIONS

We started the day with a rigorous networking hike around the Walden property. A steady uphill climb among the leafy coastal oaks, let us breathe and introduce ourselves in a relaxed style as a group of individuals from diverse backgrounds and fields joined the discussions.

Common Threads in Shared Stories

What would you do more of, if time and money was unlimited?

Become more daring

Save more trees

Be joyful.

I already live my life in abundance.

Explore love and seek enlightenment

Spark more joy and love into the world.

Focus on Intergenerational teaching

Create new projects

Be completely in the now

Regenerative communities

More love and caring.

Focus on making the earth sustainable

Expand awareness

Cultivate a quantum connection

Teach others reverence for all beings

Empower communities without leading them

Learn more tolerance and patience

Cultivate more friendships

“This world of ours... must avoid becoming a community of dreadful fear and hate, and be, instead, a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.”

“We use a design-thinking format around the table, walking discussions on nature trails, and guided meditation to inspire the group to solve big problems. Instead of the hyper-intense networking of your typical conference, participants spend the entire day outside with a carefully curated small and diverse group of people.”

After the Gathering intro, members presented current issues, focused on:

History

Nature

Self

Desire

During these discussions, participants break up into groups to increase contributions and engagement. Topics are addressed, opinions are shared and summaries are presented to all.

Community

It has been suggested by anthropologist Robin Dunbar that the number of people we are capable of maintaining meaningful relationships with is a function of the size of the brain that we have - furthering that conclusion to include theximate ideal size - a 150 person community.

During the 1990s, while Dunbar was researching primates' social grooming habits, he noticed a correlation between the size of primate brains and the number of social groups they formed as a result. In fact, he found that the larger an individual's brain is, the larger the group that it forms. This is because the larger the brain is (specifically the larger the size of the neocortex - the part of the brain that has recently evolved and is responsible for higher functions like sensory perception, conscious thought, and language). By taking the correlation between the number of people that can maintain meaningful relationships with one another and extrapolating it to the size of our brain, Dunbar came up with a famous prediction that has become known as Dunbar's number: the number of people that one can sustain meaningful relationships with is approximately 150.

We should keep in mind, though, that this number is only an estimate, as Dunbar readily admits himself. Those findings suggest that, with a 95% confidence interval, the ideal size of the group lies within the range of 100 to 230 people, yet 150 does seem to be quite relevant.

A study by Malcolm Gladwell in his bestselling book The Tipping Point showed that Dunbar looked at 21 hunter-gatherer societies for which there is evidence, from the Walbiri of Australia to the Tauade of New Guinea to the Ammassalik of Greenland, and found an average village size of 148 people. It would also be accurate to say that the same rule holds true for military fighting units of the past and present, which follow the rule of thumb that a fighting unit should not be larger than 200 in number. There is a long-standing tradition among the Hutterites, a self-sufficient religious group, for a village to be split in two at the age of 150, a practice that originated centuries ago.

In terms of the size of our neocortex, humans are capable of maintaining about 150 stable relationships with one another. It is important for us to look at this as a starting point for figuring out how to build community - at least we know what we are working with when we are starting out. Although our relationships with those 150 people will obviously differ a great deal based on how close we are to each of them based on the extent of our closeness to them. Fortunately, Dunbar and his colleagues have further broken down the number into layers based on how close the relationships are, and this is where we can begin the fun part of building community consciously.

Nature As a Catalyst

Natural Communities

Forest ecologist Suzanne Simard's groundbreaking research shows that different species indeed do rely on biodiversity for their livelihood and, in fact, communicate and share resources such as carbon, water and other nutrients through threadlike fungi (called mycorrhizas) that envelop and fuse with the tree roots. These threads link nearly every tree in a forest. Older trees take care of the younger developing trees, no matter what species. Seedlings that become disconnected from the network often do not survive. When Simard began this research almost 30 years ago, her male peers didn't understand why she would choose to study communication amongst the trees rather than growth and yield. Now her findings and highly regarded and have inspired completely new lines of research.

To learn more about the benefits that these mycorrhizas provide, the importance of healthy trees and soil in saving us from global warming, and how the practice of regenerative agriculture helps keep carbon in the soil - where it belongs - I highly recommend the film Kiss the Ground.

The trees also communicate with us. The practice of Shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, was developed in Japan, which has just about the highest life expectancy in the world. It has become a foundation of preventive health care and healing in Japanese medicine. Forest bathing creates calming neuropsychological effects through changes in the nervous system, reducing the stress hormone cortisol and boosting the immune system. After just 15 minutes of forest bathing, blood pressure drops, stress levels reduce, and concentration and mental clarity improve.

If trees could speak, what would they say?

“What I see in Nature is a grand design we can understand only imperfectly, one with which a responsible person must look at with humility.”

Key Themes

What is a community?

How is one included?

How can Nature act as a catalyst?

How can we create community?

Your Community is Much Greater

As a result of the research conducted at Brigham Young University regarding longevity, it has been discovered that the top two predictors of survival are two aspects of our social lives that are distinct, but related.

Close relationships - These are the individuals within your immediate circle with whom you have an intimate relationship. Those are the individuals you would be able to rely on to take you to the doctor, serve as a calming presence when you are experiencing an existential crisis, or pick you up when your vehicle breaks down. Similarly, the Grant Study at Harvard found that intimate relationships are related to mental and physical health. In the midst of life's ups and downs, they serve as a protective balm.

The larger circle - Another aspect of our social lives that predicts longevity, even more strongly than close relationships, is social integration. This is the number of people you interact with as you go about your daily activities. In addition to the people who are particularly close to you, this also includes the relationships that are not as strong but still constitute your wider community. Are you familiar with the person who makes your coffee? Are you familiar with the person who walks his dog by your house every morning? How about the person who grows the food you consume? What kind of book club or game night do you belong to? It has been found that the strength of these bonds is highly correlated with life expectancy.

Layers

During a recent interview with Scientific American, Dunbar stated that human social groups are structured in a series of layers that extend beyond the number 150. The average person has one to two special friends, five intimate friends, 15 best friends, 50 good friends, 150 ‘just friends,’ and 500 acquaintances.

Our relationships form a series of expanding circles of increasing size and decreasing intensity and quality of the relationship.”

The existence of these layers has been confirmed by studies of phone records, and, more recently, by studies of Facebook activity.

A 2007 study by Dunbar and his colleagues at the Oxford University looked at a set of 6 billion calls made by 35 million people from an unnamed European country and used the data to make a number of conclusions. It was at a time when cell phone calls were still one of the primary avenues that people used to communicate with one another, before the widespread use of messaging apps and social media sites. They used clustering algorithms to analyze the results of the study, and one of the ways they did it was by counting the number of calls each person made to his or her contacts.

According to the average cumulative layer, there were 4.1 people, 11.0 people, 29.8 people, and 128.9 people in total.

“These numbers are a little smaller than the conventional numbers for Dunbar layers, but within their natural range of variation,” the researchers said.

Considering that cell phone data only covers a portion of a person's total social interactions, it seems reasonable to assume that the number is slightly smaller than what is actually collected.

In a similar study, Professor Dunbar led a project that tracked the connections between two groups of more than 3,300 people in the UK using Facebook. On average, the first group of participants had 155 Facebook friends whereas the second group had 183 friends on average. The most interesting part of this study was the fact that when asked how many of their friends they could turn to if they were in distress, people answered with an average of 4. Interestingly, when asked how many people they could turn to for sympathy, people answered 14 - a number that mirrors the number of levels of friendship that exist.

Shift Your Focus Outwards

Psychologists say that your best course is to actually shift your focus outward. Performing acts of kindness and expressing gratitude are two practices that are healthy and beneficial for our emotional well-being, especially in a time when we are forced to be more isolated.

“A healthy social life is found only when, in the mirror of each soul, the whole community finds its reflection, and when, in the whole community, the virtue of each one is living.”

Turning Ideas Into Solutions

WALDEN GATHERINGS ARE NOT JUST FOCUSED ON TALKING ABOUT SOLUTIONS, BUT PUTTING SOLUTIONS INTO ACTION.

While ideas are shared throughout the day, we gather to create change.

In order to improve the world around us, we must not only speak about the issues at hand, but work towards solutions. The point of the discussions is to establish the framework for identifying and understanding the problems.

What follows, is most important.

Emerging Ideas

WHOLE SYSTEM REBOOT: We need a holistic, comprehensive overhaul of the human condition. Climate change is but one symptom of a patently dysfunctional human political economy and culture. We can’t address just one problem, e.g., climate change, we need a whole system reboot - new ways of valuing, relating, recreating, transacting, contributing, educating, worshipping, parenting, providing, etc.

COMMON GOAL: The common goal / standard of success for any organized action or community is that everyone has their basic needs reliably and sustainably provided (safety, food, water, shelter, touch) by the collective and through their contribution. From this place we can unlock human flourishing at scale. This came up in just about every discussion.

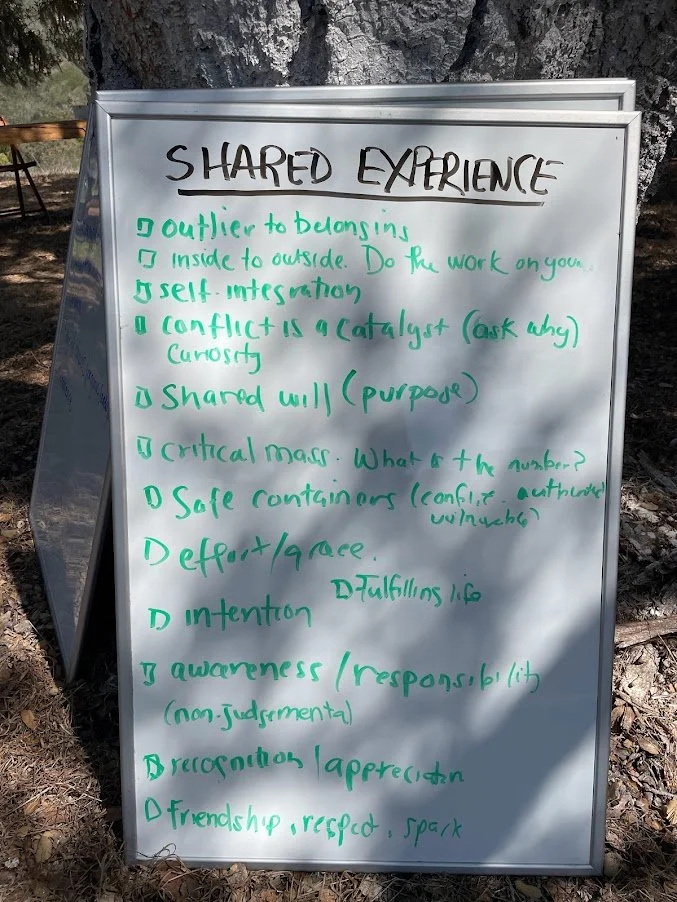

COMMUNITY BEST PRACTICES: The practices that surfaced included having a shared purpose with a huge felt emotional impact, embodying interconnectivity / interdependence / interbeing, a sense of urgency / being all-in / this or death, being open and accepting, having conflict resolution protocols, stress management practices integrated into the natural world, artful expression encouraged (with lots of storytelling), and decision-making protocols that were neither purely autocratic nor consensus-driven.

CORE THEMES: As we spent more time with the solutions we generated, a few core themes arose - love, connection, change and community. The solutions that had the most juice centered around culture and education, with two groups emerging, one with a more masculine / system / policy / resources / macro focus, and another with a more feminine / relational / creativity / emotional / micro focus.

SOULFUL COMMUNITY: A community where all the kids are raised by all the adults. We move away from a nuclear family way of living which clearly isn’t possible, practical or enjoyable (100 hrs of parents out of the home, kids raised by screens, isolated, lonely, consumerist, car-heavy, indebted way of life) to multifamily communities with interwoven, joyous connection, shared responsibilities for children, economic sustenance, culture. Near-term actions: a forum to discuss how to implement and get feedback, a call to artists and children to visualize what this could look and feel like, begin by having elders in schools to transmit wisdom.

GENERATIVE FISCAL POLICY: Halve the current US defense budget. Of this new budget, allocate a quarter to new schools, e.g., Lebron James schools, a quarter to universal basic income, a quarter to the peace corps and a quarter to ensure that teachers make as much as people who work on Wall Street. Near-term action: Have a zoom call to discuss implementation.

“We need the tonic of wildness...At the same time that we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be indefinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed by us because unfathomable. We can never have enough of nature.”

The group solution summarized:

We need a new economic model that uses the soil as fiat currency not $s.

Reciprocal support communities

Nature as antifragile

Team

We aim to bring together passionate individuals, groups and organizations to gather, learn and collaborate in small groups on how best to contribute and invest their time, talent and resources to innovative solutions -- and then take them back into the world. We see everyone who joins as an equal expert at the table because we believe in the wisdom of the crowd to find solutions.